|

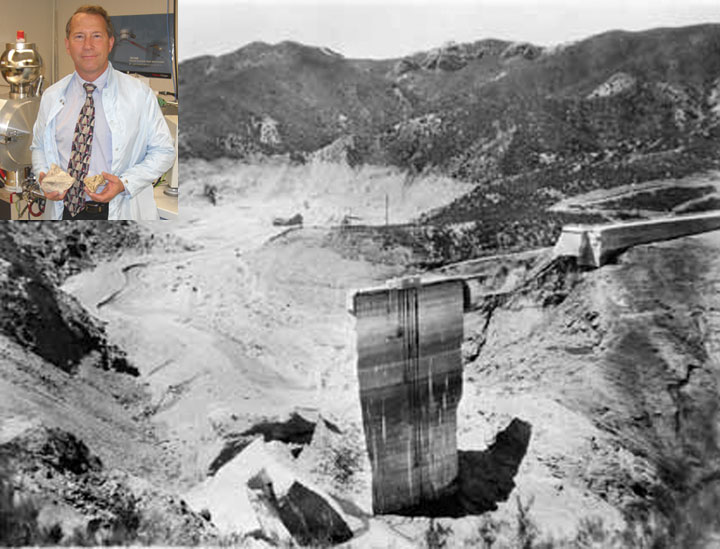

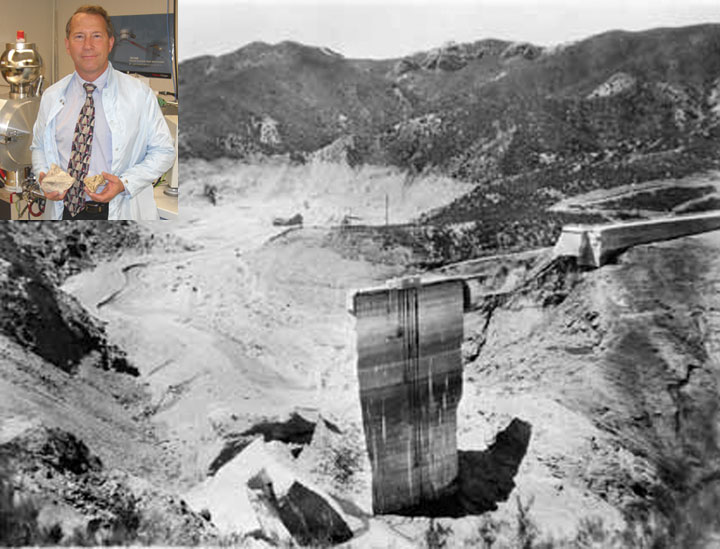

This is what is left standing following the St. Francis Dam collapse March 12, 1928. Floodwaters rushed down the Santa Clara River, devastating communities along the way and taking many lives (photo above courtesy of JohnNicholsGalley.com). (Inset) Thomas McMullen, Director of the University of Maryland CMPS/College of Computer, Math and Physical Science, holds pieces of the St. Francis Dam, the focus of his Master of Science thesis that centered on inferior concrete and faulty construction as the cause of the disaster.

|

St. Francis Dam Disaster: Today is 82nd anniversary of avoidable tragedy

March 12, 2010

By Peggy Kelly

Santa Paula News

Fourth in a series of articles exploring the St. Francis Dam Disaster

When night blankets Los Angeles, an area near Riverside Drive and Los Feliz Boulevard comes alive with colored-lights and cascading waters, a spectacular display courtesy of the William Mulholland Memorial Fountain. Set amid nearly four acres, the fountain is a fitting tribute to the man who corralled other peoples’ water to quench the thirst of a growing Los Angeles.

Of course, Mulholland’s efforts also managed to bring even more cash to the wallets of a small group of rich and powerful men, whose parched greed could never be doused.

So revered was - and remains - Mulholland that more than 3,000 people attended the August 1, 1940 dedication of the fountain. The Los Angeles Police Band played for the enthusiastic crowd, the city’s Civic Chorus raised their voices in praise, important men whose very presence conveyed wealth made flowery speeches.

The most important and wealthiest among them, Los Angeles Times Publisher Harry Chandler was also on hand to pay tribute to the man who had been his personal and his newspaper’s favorite Angeleno. Chandler had much to be thankful for, but left unsaid was that he had been a principal shareholder of the San Fernando Valley-owned syndicate whose dreams of development became a reality with the 1913 opening of Mulholland’s 223-mile Aqueduct.

Nearly 90-feet in diameter, the fountain’s colorfully lit waters reach 50-feet in the air. Nearby a bas-relief bust of Mulholland rests on a monument, his handsome brow still-tough Irish, his intelligence evident among the gentle ripples of the work across his forehead.

The Department of Water & Power, without special emphasis on the most important latter word, also has a monument sign.

It was March 30, 1940 that one of Mulholland’s granddaughters - not the one who decades before had been the focus of a nasty custody court battle gently covered in Chandler’s Times - wielded a ceremonial shovel to signify the beginning of the project. In August another granddaughter - again not the one whose custody was ultimately obtained by Mulholland - pushed the button that activated the fountain’s pump.

The fountain was completed a little more than five years following the 79-year-old Mulholland’s July 22, 1935 death from old age, disappointment and a broken heart.

Unmentioned at either event was that just 12 years before another water holder, the Mulholland-designed and constructed St. Francis Dam, had collapsed, destroying the Santa Clara River Valley, its waters also dancing as it crashed through the narrow San Francisquito Canyon, and ultimately killing what could be as many as 1,000 people. Many of the dead probably didn’t know about the dam nestled in the canyon, started in secret in 1926 and completed and destroyed in record time.

The dam collapsed March 12, 1928, a few minutes before midnight. With the nearby electrical power plant wiped out there were no lights, so most could not see the water until it was upon them, and for decades thereafter Mulholland’s reputation and legacy was closely guarded.

Almost all defended Mulholland, but Thomas M. McMullen, who tackled an independent study of why the St. Francis collapsed, believes the great man has to shoulder much of the blame for the disaster. And McMullen feels somewhat sorry for Mulholland, an emotion that undoubtedly would have infuriated the famous water bearer.

Now director of the University of Maryland CMPS/College of Computer, Math and Physical Science, McMullen’s 2004 Master of Science thesis was titled “The St. Francis Dam Collapse and the impact on the construction of the Hoover Dam.”

Before he began his research into the construction of the Hoover Dam McMullen, who was working towards his Masters degree in civil engineering, had never heard of the St. Francis Dam. By the time references to the disaster caught his interest and he investigated the cause it changed the focus of his thesis from construction to destruction.

From his study, McMullen found himself “surprised at the number of things” that firmly pointed away from the widely accepted “soft-shoulder” theory centered on the ancient slide the dam was constructed on. The theory has been used for decades to shift blame from Mulholland to geological issues supposedly not recognizable at the time.

McMullen was also nagged by inexplicable construction issues, and surprised at the scant and shoddy official state report on the collapse. Governor C. C. Young had ordered the report compiled by engineers and geologists, and McMullen found that after their first meeting on March 19, seven days following the collapse, the Commission completed the report in five days, before the disaster was even two weeks old.

All that short while Chandler’s Los Angeles Times was running thundering editorials warning people not to rush to judgment, and noting that no matter how long it took, what happened to the St. Francis Dam must be investigated to the fullest extent. To the fullest extent, at least in the case of the governor’s report, was 13 pages of engineering team-written material, two pages each of Governor Young’s letters, and rock and concrete tests, as well as 31 pictures and maps of visual filler.

Not surprising to McMullen was the report concluded the failure was due to defective foundations and stated there was nothing to indicate the accepted theory of concrete gravity dam design was in error when built upon even ordinary bedrock. Most importantly to McMullen, the report noted that water storage - so vital a California resource - must and would hereafter be subject to the police powers of the state, a conclusion he said, “mirrored the tone” of Young’s report instructions.

McMullen’s thesis noted many important details in the governor’s ordered report were not factored in, or were glossed over, such as the “unimportant” leaks through the main structure and wing wall, a discrepancy in foundation depths, the lack of an entire dam drainage system to relieve uplift pressure, and the lack of grouting. The concrete itself, noted McMullen, was “immediately excluded from having played a part in the disaster.”

Geology of the dam site was what most concerned the Commission, whose report largely focused on the canyon walls and streambed. The Commission concluded defective foundations were what brought the St. Francis Dam down, and about 75 years elapsed before McMullen zeroed in on the inferior concrete coupled with shoddy construction as the reason that “eventually caused in my opinion the failure.”

If the concrete itself had been a “of a better quality,” McMullen believes the dam “would not have fallen apart as it did. It was so filled with fractures,” the 175,000 cubic yards of concrete just broke apart under the pressure of the waters that snaked through the fissures and swirled around varied sizes and shapes of dredged stream rock, delicately suspended in worrisome air pockets. The lack of proper curing and the quality of the pour work itself was a recipe for disaster, or rather the “catastrophic failure” that McMullen said was a tragedy brewing for the Santa Clara River Valley.

For his approximately eight-month study, McMullen trekked to California, visited the site of the dam, pilfered some concrete samples and had them blind tested, which showed the extent of the sloppiness of material and preparation.

The concrete experts “investigated on a microscopic level” and found gaping air voids among the uneven aggregate taken from nearby streams by an army of shirtless men wielding shovels. Probably the quality of the concrete alone, even without being coupled with the hurry-up nature of construction that did not take into account proper curing or even grouting, made the disaster inevitable.

McMullen believes Mulholland knew there were serious problems with his St. Francis by the time the dam waters rose to 60 feet below the crest when a major leak appeared. “The dam wasn’t even filed when water was getting into this concrete, chemically breaking it down,” but McMullen said there was no turning back and no spillways to empty the structure in a timely manner.

Mulholland, who as child in Dublin, Ireland reportedly was beaten by his father for receiving bad grades - an act that led him to run away to be a seaman - was an ambitious, self-educated man who rose from ditch digger to the most important figure in the state. Nobody told Mulholland what to do, especially when it came to constructing waterworks.

And that included arbitrary changes: McMullen said the St. Francis “wasn’t even built according to the design,” with the toe substantially smaller than originally sketched, and then the dam face was raised twice during construction to accommodate another 8,000 acre feet of water added to the original storage plan of 30,000 acre feet.

When the dam burst, just days after it was declared filled for the first time, it held 12.5 billion gallons of water that, once released, traveled about 58 miles to the sea, consuming all in the way and leaving behind silt graveyards in some areas up to 70-feet-deep.

About 12 hours before his dam gave its final heave and collapsed into pieces Mulholland visited the site, summoned by the worried dam keeper who noted a widening crack running water and mud. Dams, pronounced Mulholland, always have cracks and leaks.

The statement in general was true, but in this case, said McMullen, the way the St. Francis Dam was constructed, “It just couldn’t hold the weight of the water.” And McMullen believes Mulholland knew it.

Footnote: The fifth in this series of articles exploring the St. Francis Dam Disaster will be published in the Santa Paula Times Friday, March 19.