|

Ann Stoddard Stansell of Los Angeles presented her “Memorialization and Memory of Southern California’s St. Francis Disaster of 1928” at the May 7 4th annual symposium on the subject held this year at the Agriculture Museum in Santa Paula.

|

Part I: St. Francis Dam Disaster Symposium brings new life to disaster

May 18, 2016

By Peggy Kelly

Santa Paula News

The St. Francis Dam Disaster found new life through a panel of experts at the May 7 symposium held at the Ventura County Agriculture Museum.

Sponsored by the California State University Northridge Forgotten Casualties Project, it was the first time the annual symposium was held in Santa Paula and drew about 100 people interested in the disaster.

The St. Francis Dam Disaster occurred minutes before midnight on March 12, 1928 when the dam catastrophically failed; the resulting flood of 12.4 billion gallons of water took the lives of at least 431 confirmed victims as the destruction traveled 56 miles from the dam site to the Pacific Ocean.

The waters swept through what is now Santa Clarita and through the Santa Clara River Valley, destroying millions of dollars of property.

The collapse of the St. Francis Dam is considered to be one of the worst American civil engineering disasters of the 20th Century and remains the second-greatest single loss of life in California history after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

The disaster marked the end of the career of William Mulholland, the acclaimed head of the City of Los Angeles’ Bureau of Water Works & Supply who had created the Aqueduct.

CSUN Professor Dr. James Snead, founder of the Forgotten Casualties Project (FCP), said the May 7 gathering was the fourth in a series of “our revolving roadshow” that strives for an exchange of information and ideas in an “informal setting” featuring those with and without knowledge of the dam disaster.

Water said Snead, is a “fundamental aspect of the historical life of the Old West and the St. Francis Dam Disaster is a wedge in that issue…”

Considered almost forgotten there has been a burst of interest in and books written about the disaster but the human aspect must always be a focal point of the story.

Archeologists are more than diggers he noted and the brick-a-brac of daily lives offers tremendous information about times past; records such as those still held by the Department of Water & Power have provided “incredible records,” detailing the smallest detail of the lives of victims researched by Ann Stoddard-Stansell for her thesis.

Students involved in the FCP have been working a seemingly bare landscape that still has yielded much evidence of the “fury of the disaster” but it’s the lives lost that Snead said remain the real story of the disaster.

Student Krystal Kissinger spoke of her archeological fieldwork in San Francisquito Canyon, home to the dam where some workers from the Los Angeles Aqueduct worked and lived.

Kissinger’s historical archeological study focuses on the aqueduct, built between its Owens Lake source of water and diverted to Saugus in the San Fernando Valley the site of proposed residential growth. The gravity fed aqueduct, completed in 1913, was shown on a map but the focus of her study is on the workers and their camps set up along the path of construction.

Camps were established in two separate locations in 1909-1910 and 1911-1912 with two camps in the St. Francisquito Canyon, one devoted to the aqueduct and the other constructing the power stations.

Camps were built on terraces on a hillside where Kissinger and others used metal detectors and other methods of discovering what everyday life was for the workers.

No matter how mundane the find might seem to outsiders Kissinger said such items “are really fun stuff for me…I never thought I’d be so excited about insulators,” and the research to identify the manufacturer and other details to add to the bigger picture.

A CSUN archival research assistant, Kissinger’s work includes documents regarding payrolls, medical treatments, purchase records and other paperwork detailing the workers — a mixture of Germans, East Europeans and Mexicans — and life in their camp.

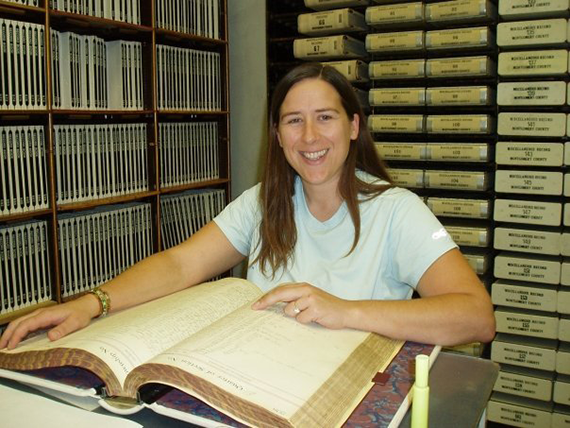

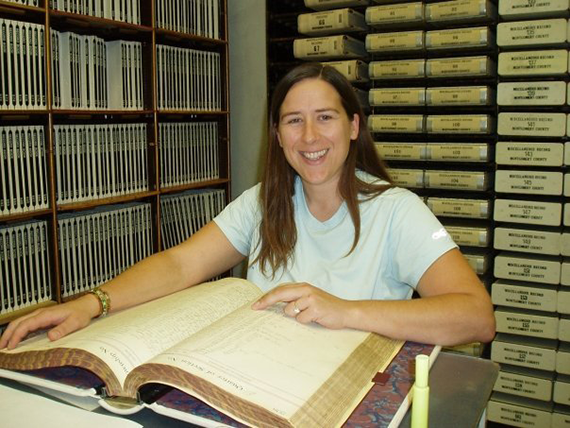

Ann Stoddard Stansell, a founding member of the Forgotten Casualties Project, showed the result of extensive research for her thesis, Memorialization and Memory of St. Francis Dam Disaster of 1928.

Hers is the first documentation of the victims and the forms of commemoration used for them and the disaster itself including songs, ballads and “other forms of folklore…”

The disaster had been “largely forgotten” outside the flood corridor until the 1960s when Santa Paulan Charles Outland wrote “Man Made Disaster” which created interest in the flood and its victims.

Stansell’s quest in documenting those killed in the disaster encompassed documentation including death records, photographs, survivors’ memories and DW&P records. In Southern California she tracked each fatality from cemetery to cemetery documenting each commemorative marker; Stansell also utilized Internet gravesites and developed a nationwide network of volunteers who took photos of those buried in their areas — including Hawaii — for her.

She told symposium attendees that Los Angeles paid $150 to each victim’s family for burial costs, and Southern Pacific Railroad shipped those to be buried out of state free to their final resting place.

Stansell spoke of William Mulholland, who without oversight constructed the St. Francis Dam, the creator of the aqueduct and the Mulholland Dam that after the disaster was “rebranded” as the Hollywood Reservoir.

Self-taught engineer Mulholland, who visited the dam site in response to the worries of the dam keeper just 12 hours before the collapse and proclaimed it sound, took full responsibility for the incident although he remained “arrogant to the end…”

Stansell detailed the loss of life mile by mile as the 12 billion gallons of floodwaters which created a “huge whirlpool” swept away everything in its path.

Eight morgues were set up for the victims as heartbroken people went from one to another to find lost loved ones. Los Angeles purchased plots for the unidentified; Stansell said all bodies found in Ventura County were photographed, a courtesy not extended to those that died in Los Angeles County.

A mass funeral held in Santa Paula on March 17, 1928 drew 3,000 mourners.

Mulholland’s assistant Henry Van Norman, who visited the dam the day of the disaster with the “Chief” urged Los Angeles to settle the claims as quickly as possible noting their was a “moral obligation” — as well as looming lawsuits — that should be adhered to.

For two months in the summer of 2012 Stansell culled through more than 5,000 documents and photographs including 817 death and property loss claims.

In the aftermath, “It was about who was left behind,” and although evidence of racial discrimination in proposed payouts to Mexicans were found by Stansell she said that as soon as families secured the services of attorneys more equitable settlements were reached.

One man who lost his wife and four children received a $9,000 settlement; their grave remains unmarked.

Sixty-six victims were never identified of the 423 “maximum” victims Stansell called “souls” that lost their lives in the disaster and there are approximately 400 monuments for same, from individual grave markers and mass monuments to The Warning statue in Santa Paula.

Those with a deep interest in or who have formally studied the disaster are banded together for continuing discussions, a group said Stansell known as “Dammies…”

Part II will include the presentation by Thomas McMullen, Associate Dean/Professor of the University of Maryland. His “The St. Francis Dam Collapse and Its Impact on the Construction of the Hoover Dam” resulted from his thesis research into the Hoover Dam. When McMullen saw several references to the St. Francis Dam Disaster it piqued his interest leading to his startling dissertation.

Santa Paula journalist Peggy Kelly presented “Thornton’s Wild Ride! The True, Untold and Unbelievable Story of the Hero of the St. Francis Dam Disaster” about Thornton Edwards, a State Motor Officer and the city’s former police chief credited with saving many lives.

Photographer and author John Nichols — who wrote “The St. Francis Dam Disaster” and amassed the disaster collection now owned by the Ventura County Museum — addressed digital storage/curation issues of historical photographs including those of the dam disaster.